Survey of Youth and Young Adults on Vocations: Background

Consideration of Priesthood and Religious Life Among Never-Married U.S. Catholics by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University - Washington, D.C.

Background

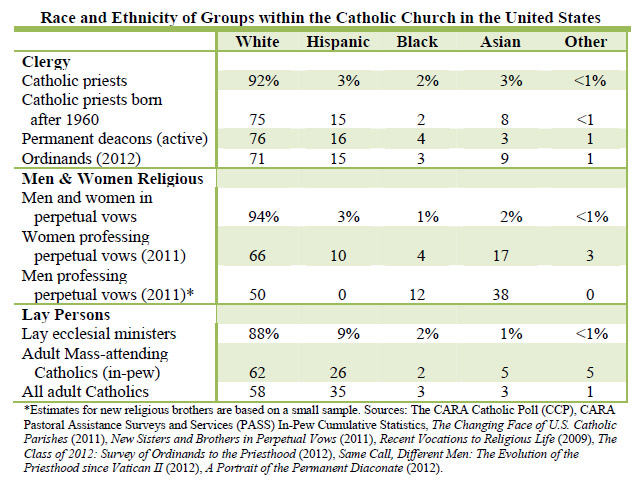

In the second decade of the 21st century, Catholic clergy, men and women religious, and lay ecclesial ministers in the United States predominantly self-identify their race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic white. At the same time, the racial and ethnic makeup of Catholics in the pews is markedly different. How can one explain the racial and ethnic disproportionality of Catholic leaders to Catholics in the pews or to the overall population of Catholics in the United States?

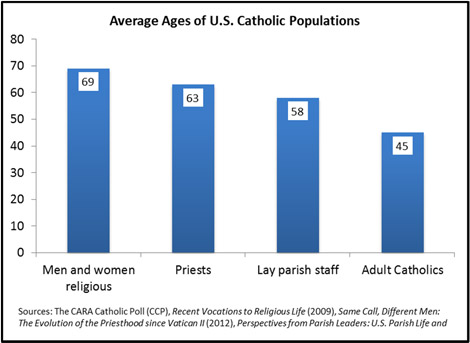

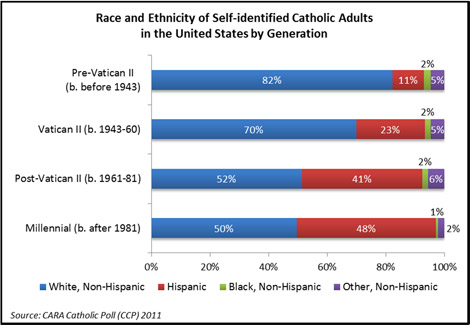

Among those currently in leadership positions in the Church, many began their ministry decades ago and are of the Pre-Vatican II (born before 1943) and Vatican II (born 1943 to 1960) generations. About seven in ten or more Catholic adults of these generations self-identify their race and ethnicity as non-Hispanic white. The average ages of priests and men and women religious are in their 60s and 70s; by comparison, the average age of adult Catholics in the United States is 45.

Much of the portion of the adult Catholic population that is most racially and ethnically diverse has not reached an age at which they are likely to enter ministry or seek a vocation. The most racially and ethnically diverse generation in the Catholic population are the Millennials (born after 1981). This group did not begin to turn 30 until 2011. Most men being ordained to the priesthood and men and women entering religious life now are in their 30s. Most Catholics serving on a parish staff report that they did not hear a call to ministry until they were in their 30s.

The racial and ethnic makeup of the recently ordained and those professing perpetual vows in recent years is much more reflective of the diversity in the general Catholic population. 8 Yet, some disproportionality remains—especially for Hispanic Catholics. Hispanics are the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population and the Catholic population as well. 9 As Matovina notes, “no past or present group has had such a dearth of clergy vocations relative to its size as do Latinos” (p. 136). 10

Although generational differences explain much of the disproportionality between Catholic leaders and the Catholic population, there are likely other factors that may be limiting the growth of vocations among Hispanics. Yuengert notes that “Dioceses which are more heavily Hispanic…have lower ordination rates” (p. 296). 11 Ospino finds that “The number of Hispanic bishops, priests, permanent deacons, and vowed religious is growing, yet at a very slow pace” (p. 30). 12 Martínez argues that “The lack of Hispanic clergy and skilled lay leadership within a situation of an ever-continuing shortage of Catholic priests and religious is seriously compromising the future. Recent surveys indicate that the special religious needs of the Hispanics are cultural in nature” (p. 85). 13

What are the roots of Hispanic underrepresentation other than generational differences? There is a pressing need for the Church to understand these factors as Millennials reach the age at which they may begin to enter Church ministry and service. The literature specifically on this topic is sparse.

The Immigrant Experience

Research regarding Hispanic Catholics in the United States often focuses on the topic of the immigrant experience and integration of Hispanics into parish life. Fitzpatrick notes that “the lack of Hispanic clergy is critical” to understanding this dynamic (p. 160). 14 Many Catholic immigrants from Europe in earlier years came to the United States with clergy from their home country. This has not been the case with Hispanic immigration in the last few decades. As Fitzpatrick notes, “The creative response of the Church to immigrants in the last century was the creation of the national parish. This was a parish, German let us say or Italian, founded by German or Italian priests, where the life of the parish became a transfer into the new world of the central institution of the lives of the immigrants in their homeland. The same language was used by priests, sisters, brothers of the same cultural background” (p. 161).

This experience was not replicated for Hispanics as, “Bishops have been reluctant to establish ‘national parishes’ for Hispanics. One important reason is that their own priests are not coming with the newcomers to demand the formation of these parishes” (p. 161). Instead, Hispanic Catholic immigrants have more often than not been a part of an “integrated parish” where there is “a Mass in Spanish, sometimes in the lower church, sometimes in a parish hall or chapel; and pastoral services (baptism, marriage, burial) and devotions in Spanish often by a priest who has learned Spanish and is familiar with the cultural background of the Hispanic parishioners. This is a practical, but not an ideal solution” (p. 163).

In practice this process was fraught with problems and inconsistencies. Deck notes, “The resistance educated Catholic leaders, whether clerical or lay, have shown to popular religious expressions has been deep and extensive.” 15 As Sandoval describes, “In some dioceses, the Cursillo in Spanish was prohibited for a time. In some areas, pastors resisted offering the Mass in Spanish” (p. 118). 16 Matovina notes some opposed Cursillos because they felt these “can drain parishes of their most active and talented leaders, who prefer to work in the more satisfying ministries of the Cursillo than the everyday but necessary concerns of the parish” (p. 112). He adds that “one is hard pressed to find a Latino Catholic leader, especially those active during the first fervor of the movement in the 1960s and 1970s, who has never had any involvement or contact with the Cursillo” (p. 112).

Levitt notes that “the Catholic Church today fosters segmented assimilation rather than the complete assimilation it encouraged in the past. It incorporates Latinos into an Anglo-dominated institution while allowing them—and in some cases encouraging them—to remain ethnically apart” (p151). 17

Given this often inconsistent pattern of integration Odem notes that “Scholars of Mexican and Latin American immigration to the United States…have not viewed the Catholic Church as a major source of community empowerment.” (p. 28). 18 At the same time, things have improved more recently and she also argues that “As a result of changes in church policies brought on by Vatican II and the organization and protests of Latino clergy and lay leaders, the United States Catholic Church has become more responsive to Latino Catholics in the last few decades.” (p. 29). Gautier et al. explain that “It is no secret that both the Catholic Church in the United States and the priesthood itself are becoming increasingly multicultural. It is now commonplace, especially in the southern and southwestern dioceses of the United States, and in almost all large cities throughout the country, to find bilingual parishes where Mass is celebrated in both English and Spanish” (p. 92). 19

Research by Gray et al. on parish life in the United States indicates that “One in three parishes (29 percent) celebrates Mass at least once a month in a language other than English. This is an increase from 22 percent of parishes in 2000. Most of these Masses, 81 percent, are in Spanish. Overall, about 6 percent of all Masses (weekday and weekend) are celebrated in Spanish.” 20

Despite these changes, Matovina reminds that there are still challenges for more recent immigrants as “most had endured the ordeal of migrating from their homelands to blighted neighborhoods in U.S. cities, where they found relatively few priests prepared to serve them in their native tongue” and that many still face hostility generally in their communities and even “from members of their own church” (p. 42).

To the degree that Hispanic Catholics have felt or continue to feel marginalized in any way in parish life, one might expect there to be less interest in Catholic vocations among Hispanics.

Cultural Differences

Others have noted important cultural differences that may be related to Hispanics being less interested in seeking vocations. Christiano highlights the notion that “Hispanic Catholicism is rooted in a richly textured folk piety that is conveyed through common people (not priests) and centered in the home (not the church)” (p. 56). 21 Levitt concurs, noting that among Hispanic Catholics, “beliefs were manifested through popular religious practices that constitute the core of Latino religious life and that are often engaged in outside the formal church” (p 152). Matovina adds “the epicenter of Hispanic Catholicism and Hispanic Catholic ministries is the home and extended family” (p. 101).

Outside of the home, Hispanic Catholics have not always relied on their parish first. Hughes notes that “Hispanic Catholics have weak institutional ties to the Catholic Church” (p. 364). 22 Matovina cites the importance of “apostolic movements along with other small ecclesial communities” (p. 101). As Espinosa notes “The decline in native Latino Catholic clergy along with an increase in Mexican immigration between 1880 and the 1940s created a leadership vacuum in the Latino community that was filled in large part by not only Catholic lay activists but also by Latino mutual aid societies (mutualistas) like the Alianza Hispano Americano (1894) and the Sociedad Caballeros de Nuestra Sefiora de Guadalupe (ca. 1927)” (p. 154). 23 Matovina highlights the importance of Catholic Charismatic Renewal (CCR) as “the most widespread apostolic movement among Latino Catholics today” which is centered on prayer groups—most often lay led—that are just as likely to meet in a home as in a parish setting (p. 113). At the same time, this participation in faith outside of the parish should not be interpreted as a rejection of the Church or parish life. Indeed many active in CCR have very traditional beliefs and practices and are supportive of their local parish (Matovina, p. 117).

Yet this greater relative detachment from the institutional Church, parish, and from clergy may have made the priesthood less visible as a vocation among Hispanic Catholics. Also, the effective presence of lay leaders may have demonstrated to many Hispanic Catholics the contributions they could make to their faith and communities outside of the traditional vocations of the priesthood or religious life. Others have noted the relative shortage of priests in many Latin American countries (Tibesar p. 413, Pelton p. 1). 24 To the degree that this is rooted in culture, one would expect this to also be reflected in the beliefs and practices of immigrants from these countries.

Gray and Gautier note that, “Male Latino Catholics are less likely than male non-Latino Catholics to agree that they have ‘ever known a Catholic priest on a personal basis, that is, outside formal interactions at church or school’ (47 percent compared to 61 percent). To the degree that they have had less personal exposure to priest role models, they may be less aware of the vocation as a personal option.” 25

Writing in 2006, Gray and Gautier also find that, “male Latino Catholics are less likely than male non-Latino Catholics to say they have ever considered becoming a priest or brother, and in the past four years they seem to have become even less likely to do so. At the same time, this reluctance appears not to be based on some growing negative assessment of priestly vocations. Instead it seems to be more grounded in their personal view that they themselves [emphasis added] would not consider being a priest.”

Gray and Gautier highlight a possible cause for this lack of consideration in the requirement for celibacy. “Another factor may be differing cultural responses to the requirement of celibacy. There is no significant difference between male Latino Catholics and male non-Latino Catholics in their level of agreement with the statement, ‘Have you ever considered serving in the Church as a lay minister?’ In this case, celibacy is not a requirement for lay persons (who are not vowed religious). However, this does not imply that male Latino Catholics would more seriously consider priestly vocations if celibacy were not a requirement. In fact, male Latino Catholics are much less likely [emphasis added] than male non-Latino Catholics to agree that ‘married men should be ordained as priests’ (47 percent compared to 73 percent).”

Matovina summarizes, “Explanations of the lack of Hispanic vocations include kinship ties that deter prospective candidates from leaving the family circle, the requirement for mandatory celibacy, and particularly scant educational opportunities that leave many ill prepared for the ordination requirement of completing a Master’s degree” (p. 136). The latter factor represents a critically important institutional barrier.

Institutional Barriers

Ospino finds that as many as 70 percent of Hispanics that are active in Church ministry are first generation immigrants. Thus, immigrants are very quick to take up leadership roles but many lack some of background and education that parishes in the United States require for advancement or the seeking of a vocation. “The work of these leaders is often constrained by their own limitations: many speak only Spanish. …. Many do not know how ‘the system’ works and thus lack the basic knowledge to network within their dioceses, parishes, and other ecclesial and social organizations” (p. 180). Ospino also regrets that the Church appears to not be connecting with potential leaders in the second and third generation creating a “skipped” generation (p. 181).

Yet, the biggest barrier may be in education requirements. As Ospino notes, “the majority of Latino/as in the United States have very low levels of formal educational attainment, a situation that puts them in positions of extreme disadvantage” (p. 181). He concludes that “the number of Latino/as who can respond to the call to ministry within current ecclesial structures and actually succeed is very small” (p. 182).

CARA’s national surveys of adult Catholics reveal that not only are Hispanics less likely than Anglo Catholics to have a college education, they are also less likely to have ever been enrolled in a Catholic school at any level. Thus, they may be less likely to be aware of vocational opportunities or to know clergy or vowed religious outside of the parish setting.

Matovina notes that even those who meet educational prerequisites may find the seminary environment difficult. “For Hispanic young men who do sense a call to priesthood, further obstacles include an institutional culture in seminaries that often is not conducive to Hispanic emphasis on ‘personal contact and trust’ and, for some, a lack of legal immigration status that in many dioceses precludes them from pursuing seminary studies” (p. 137).

Awareness of these institutional barriers has led many bishops to alter the recruitment process in a way that makes this more inviting to and supportive of Hispanic candidates. As Matovina notes these efforts have produced results in recent years (p. 139). This is reflected in the growing proportions of new ordinands who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino. Despite this success, Matovina concludes “the shortfall of Latino clergy remains urgent” (p. 141).

Footnotes

- Dean R. Hoge’s The First Five Years of the Priesthood (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002) documents a rise in new Hispanic priests beginning in the 1990s.

- As Allen Figueroa Deck importantly cautions, “Hispanic” or “Latino” are umbrella terms which are incapable of communicating the diversity of people who self-identify as such (“The Spirituality of United States Hispanics: An Introductory Essay” U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 9, No. 1/2, Hispanic Catholics: Historical Explorations and Cultural Analysis (Winter - Spring, 1990), pp. 137-146). For example, immigrants from Latin America more often self-identify with their nationality and there are many differences in the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of people of these different nationalities.

- Matovina, Timothy. Latino Catholicism: Transformation in America’s Largest Church. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Also citing research by Richard Schoenherr and Lawrence A. Young, Full Pews & Empty Altars. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993. Yuengert, Andrew. “Do Bishops Matter? A Cross-Sectional Study of Ordinations to the U.S. Catholic Diocesan Priesthood” Review of Religious Research, Vol. 42, No. 3 (Mar., 2001), pp. 294-312.

- Ospino, Hosffman. Hispanic Ministry in the 21st Century: Present and Future. Miami: Convivium Press, 2010.

- Martínez, Germán. “Hispanic Culture and Worship: The Process of Inculturation” U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 11, No. 2, Evangelization and Culture (Spring, 1993), pp. 79-91.

- Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. “Catholic Responses to Hispanic Newcomers” Sociological Focus, Vol. 23, No. 3, Special Issue: Theory and Research in Applied Sociology of Religion (August 1990), pp. 155-166.

- Deck, Allan Figueroa “The Spirituality of United States Hispanics: An Introductory Essay” U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 9, No. 1/2, Hispanic Catholics: Historical Explorations and Cultural Analysis (Winter - Spring, 1990), pp. 137-146

- Sandoval, Moises. “Hispanic Immigrants and the Church: 1948 to the Present” U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 9, No. 1/2, Hispanic Catholics: Historical Explorations and Cultural Analysis (Winter - Spring, 1990), pp. 105-118.

- Levitt, Peggy. “Two Nations under God? Latino Religious Life in the United States” Latinos Remaking America. Eds. Marcelo M Suarez-Orozco and Mariela M. Paez. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002.

- Odem, Mary E. “Our Lady of Guadalupe in the New South: Latino Immigrants and the Politics of Integration in the Catholic Church” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Fall, 2004), pp. 26-57.

- Gautier, Mary L., Paul M. Perl, and Stephen J. Fichter. Same Call, Different Men: The Evolution of the Priesthood since Vatican II. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2012.

- Gray, Mark M., Mary L. Gautier, and Melissa A. Cidade. The Changing Face of U.S. Catholic Parishes. Washington DC: National Association for Lay Ministry (NALM), Emerging Models of Pastoral Leadership Project, 2011.

- Christiano, Kevin J. “Religion among Hispanics in the United States: Challenges to the Catholic Church” Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 38e Année, No. 83 (Jul. - Sep., 1993), pp. 53-65.

- Hughes, Cornelius G. “Views from the Pews: Hispanic and Anglo Catholics in a Changing Church” Review of Religious Research, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Jun., 1992), pp. 364-375.

- Espinosa, Gastón. “’Today We Act, Tomorrow We Vote’: Latino Religions, Politics, and Activism in Contemporary U.S. Civil Society” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 612, Religious Pluralism and Civil Society (Jul., 2007), pp. 152-171.

- Tibesar, Antonine. “The Shortage of Priests in Latin America: A Historical Evaluation of Werner Promper's Priesternot in Lateinamerika” The Americas, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Apr., 1966), pp. 413-420. Pelton Robert S. “A Church in Flux” Notre Dame Magazine, Winter 2007–08. https://magazine.nd.edu/news/1345/

- Gray, Mark and Mary Gautier. “Latino/a Catholic Leaders in the United States.” A research note later published in Emerging Voices, Urgent Choices: Essays on Latino/a Religious Leadership. Brill Academic Press, 2006.